|

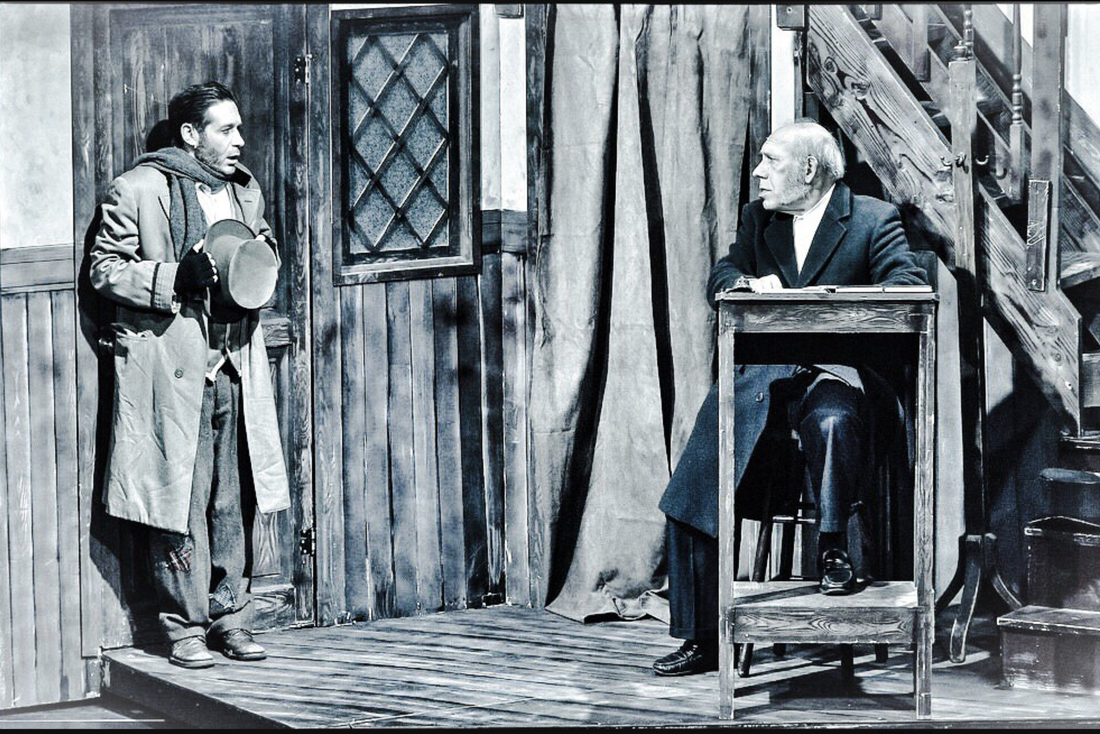

Adam Nelson is a revelation as Bob Cratchit in "Christmas Carol" {Coaster}

There is not, in all literature, a book more thoroughly saturated with the spirit of its subject than Dickens’s “Christmas Carol,” and there is no book about Christmas that can be counted its peer. To follow old Scrooge through the ordeal of loving discipline whereby the ghosts arouse his heart is to be warmed in every fibre of mind and body with the gentle, bountiful, ardent, affectionate Christmas glow. Read at any season of the year, this genial story never fails to quicken the impulses of tender and thoughtful charity. Read at the season of the Christian festival, its pure, ennobling influence is felt to be stronger and sweeter than ever. As you turn its magical pages, you hear the midnight moaning of the winter wind, the soft rustel of the falling snow, the rattle of the hail on naked branch and window-pane and the far-off tumult of tempest-smitten seas; but also there comes a vision of snug and cosey rooms, close-curtained from night and storm, wherein the lights burn brightly, and the sound of merry music mingles with the sound of merrier laughter, and all is warmth and kindness and happy content, and, looking on these pictures, you feel the full reality of cold and want and sorrow as contrasted with warmth and comfort, and recognize anew the sacred duty of striving, by all possible means, to give to every human being a cheerful home and a happy fireside. The sanctity of that duty is the moral of Christmas, and of the “Christmas Carol.” That such a book should find an enduring place in the affectionate admiration of mankind is an inevitable result of the highest moral and mental excellence. Conceived in a mood of large human sympathy, and expressed in a delicately fanciful yet admirably simple form of art, it addresses alike the unlettered and the cultivated, it touches the humblest as well as the highest order of mind, and it satisfies every rational standard of taste. So truly is this work an inspiration, that the thought about its art is always an afterthought. So faithfully and entirely does it give voice to the universal Christmas sentiment, that it seems the perfect reflex of every reader’s ideas and feelings thereupon. There are a few other books of this kind in the world, — in which Genius does, at once and forever, what ambling Talent had always been vainly trying to do, — and these make up the small body of literature which is “for all time.” In the embellishment of these literary treasures, therefore, there is a wise economy and an obvious beneficence; and the publishers of this edition have made a most sagacious and kindly choice of their principal Christmas book for the present season. Their “Illustrated Edition of Dickens’s Christmas Carol” comes betimes with the first snow; and its beautiful pages will assuredly, and very speedily, be lit up by a ruddy glow from many a Christmas hearth throughout the land. The book is a royal octavo, containing one hundred and twelve pages, printed form large, neat, clear-faced type, on satin-surfaced paper, delicately tinted with the color of cream. It was printed at the University Press by Messrs. Welch, Bigelow, & Co., and is an enduring emblem of their skill and taste, affording as it does the best of proof that they have done their work with heart as well as hand. Its illustrations—thirty-six in number—are from the poetic pencil of Eytinge; and the engraving has been done by Anthony. These pictures, of course, constitute the novel feature of the book. A few of them are little head and tail pieces, which may briefly be dismissed as simple, neat, and appropriate. Twenty of them, however, are full-page drawings, while five smaller ones are captions for the five chapters of the story. Viewed altogether, they form the best effort and fullest expression that the public has yet seen of Eytinge’s genius. They show the heartiest possible sympathy with the spirit of the “Christmas Carol,” and a comprehensive and acute perception as well of its scenic ideals as of its character portraits. They have not only the merit of being true to the book, but the merit of representing the artist’s individual thought and feeling in respect to its momentous themes, — love, happiness, charity, sorrow, bereavement, the shocking aspects of vice and squalor, the bitterness of death, and the solemn consolations of religion. He has put his nature into his work, and it therefore has an independent and abiding life. How deep and delicate are his perceptions of the melancholy side of things may be seen in such drawings as that which depicts the miserable Scrooge, crouching on his own grave, at the feet of the Spirit, and that which shows poor Bob Cratchit kneeling at the bedside, and mourning over Tiny Tim. The pictures of Scrooge, gazing with faltering terror on the covered corpse upon the despoiled bed, and of Want and Ignorance, typified by the wretched children that are seen to wallow in a city gutter, have a kindred significance. In striking contrast with these, and expressive of as quick a sympathy with common joys as with common sorrows, are the sketches of domestic scenes, as the humble home of Bob Cratchit, — a character, by the way, that the artist has intuitively realized and reproduced from a mere hint in the story. The sentiment, the family characteristics, and the minute elaboration of accurate detail, in these Cratchit pictures, are conspicuous and admirable. No intelligent observer can miss or fail to like them. The life of the drawings, too, is abundant. In looking on Bob’s face you may hear his question, “Why, where’s our Martha?” as clearly as if his living voice sounded in your ears. This quality is evident again in the character-portrait entitled “On ‘Change,’” wherein three representative moneyed men are commenting, in a repulsive vein of hard, gross selfishness, on the death of their fellow money-grubber. This is one of the boldest and best of the illustrations. Kindred with it in force of character are the sketches of the philanthropists soliciting Scrooge’s charity, and the foul old thieves haggling over their plunder from the miser’s bed of death. Loathsome depravity of body and mind has seldom been so well denoted as in the faces in this latter drawing. Here, again, the artist has built upon a mere hint, except in the reproduction of the accessories of the dismal scene. The habit of close and constant observation of actual life, as well as of human nature, is evinced in such work as this, — a habit clearly natural to this artis, and as clearly strengthened by long, careful, and cherished communion with the works of Dickens. Perfect distinctness is one of the great virtues of those works, and that virtue reappears in these pictures. Every individual has been clearly conceived by the artist. There is but one Scrooge, even in the sketches which so hilariously illustrate his wonderful transformation. There is but one Bob Cratchit, whether carrying his little child along the wintry street, or sitting at his Christmas dinner, or bending beside the bare, cold, lonely bed of death, or staggering backward form the frisky presence of his regenerated employer. This vivid clearness of execution shows the essential control of intellect over fancy, — always a characteristic of the true artist. Fancy has none the less its full play in these drawings, and a genial heart beats under them, prompt alike to pity and to enjoy. The appreciative observer will also perceive, with cordial relish, their frequent poetic mood. One of them illustrates the single phrase, “They stood beside the helmsman at the wheel,” and is a very vivid reproduction of the mystical, awesome presence of darkness on the waters. The moon looks dimly through the clouds. The light-house lamp is shining over the dark line of distant coast. On speeds the vessel, guided by the firm hand of the resolute helmsman, with whom, as you gaze, you seem to feel the rush of the night-wind and hear the sob and plash of the wintry waves. The artist who labors thus does not labor in vain. Mr. Eytinge is the best of the illustrators of Dickens, and it is his right that this fact should be distinctly stated. His work in this instance has received the heartiest co-operation of the best of American engravers; for Mr. Anthony is not a mere copyist of lines, but an engraver who, in a kindred mood with the artist, preserves the spirit no less than the form, and who has won his highest and amplest success in this beautiful Christmas book. (The Atlantic)

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

ADAM NELSONConspirator. Archives

January 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed